There's a crack of static and then an amplified voice. “One minute!”

I’m sitting on my board in the center of a Popsicle-stick-shaped pool, which stretches nearly the length of seven football fields. The surface of the water is still and dark, a mirror reflecting the morning sky. Suddenly, I hear the banshee-like moan of cable being winched. A blue-canopied train of 150 adjoined truck tires barrels down from the far end of the pool. For a moment I feel the bystander’s urge to move away from danger. But I’ve dreamed of this moment for many months and I hold my ground.

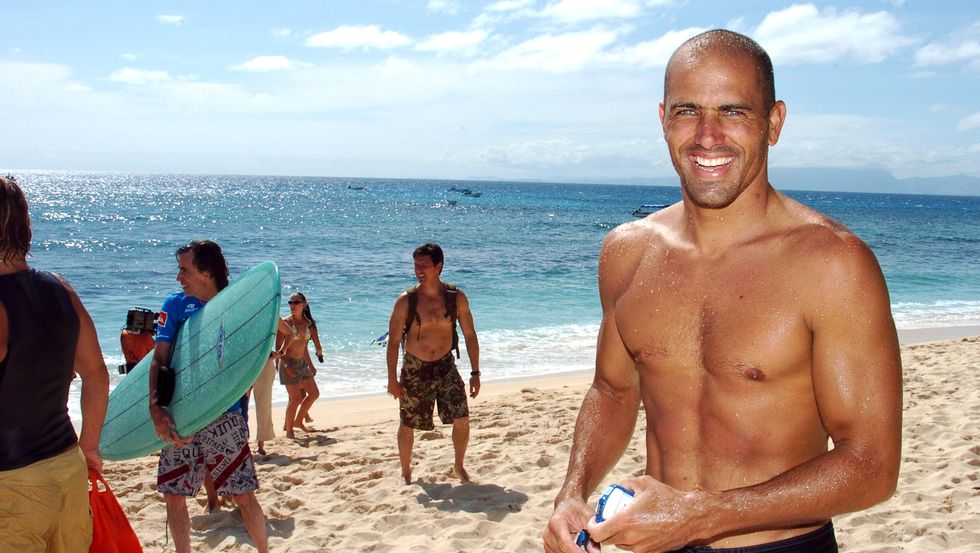

A mirage appears on the horizon: the perfect wave. It builds, then breaks. A lithe, tan, forty-six-year-old surfer springs to his feet and starts effortlessly slithering toward me. It’s his wave—the product of years of research and experimentation, millions of dollars spent in secret. It’s also his sport. Kelly Slater is the undisputed king of surfing, an eleven-time World Surf League champion. His dominance, mastery, and longevity have led some to ask whether Slater is not only the greatest surfer of all time but also the greatest athlete of all time. At the very least, he’s spent his whole life doing things that other people thought impossible. But Slater is human, middle-aged, and surfing with a broken foot, against his doctor’s advice. He falls as the foam washes over him.

I shake off the awe, frantically spin, paddle, and drop into my first inland wave. Perhaps two hundred others—among them current top competitors, billionaires, and celebrities—have felt what I’m feeling.

Historically, good surf has been a reward for the determined, available to anyone willing to suffer enough. The WSL Surf Ranch is 100 percent private, which wouldn’t matter much if the wave sucked. From Big Surf, which opened in 1969 in Tempe, Arizona, to Disney World’s Typhoon Lagoon, artificial waves have tended to resemble supersized toilets.

But Slater’s wave does not suck. It has all the qualities of a world-class ocean wave while also being uncannily predictable and endlessly reproducible, unlike any other on earth. The moment Slater unveiled his machine can be considered surfing’s singularity: the day technology surpassed nature.

Like most surfers, I can recall exactly where I was when I first heard, or rather saw, the news: at home in northern California, scrolling through my Instagram feed at the bay windows, my back to the ocean as my son tugged at my pant leg. There it was: a teaser clip of Slater riding “the best wave that anyone’s ever made.” At first I wondered if it was real. The wave looked magical, otherworldly, the stuff of CGI. I clicked through to a longer clip, replayed it a few times in silence, freezing certain frames. My son kept trying to get my attention, so I put on a pair of headphones. Text messages appeared. I swiped them away. Slater’s reaction in the video is almost as striking as the wave itself. “Oh my God! . . . No way! . . . What???” No one saw it coming—not even Slater, apparently. Most surf-world secrets don’t stay secrets for long. You hear whispers in parking lots when a top pro is strung out or a new break has been discovered. By the time it’s formally announced, it’s old news. But not this time. I’d heard nothing, not even in confidence from gossipy insiders. Hell, Slater and I have known each other for more than a decade—we met in 2007, when I was covering the world tour for the website Surfline—and I’d texted with him often. There’d been no hints. Surfers worldwide felt blindsided.

It’s not the first time Slater has changed the game he’s come to embody. Over the years, he has reinvented performance surfing, helped engineer the creation of the WSL, challenged the industry’s environmental practices, and doggedly fought to get surfing taken seriously as a sport. He has also repeatedly been called a sellout. Now Slater’s artificial wave is set to finally bring the sport into the “inlander” mainstream, and to make the vagaries of nature as mechanical as a batting cage, permanently redefining what surfing means in the process. While a debate raged on social media as to whether his wave would save surfing or destroy it, the only thing everyone could agree on was that nothing would ever be the same. “It’s the biggest shift in the history of surfing, obliterating any other event,” says Matt Warshaw, author of The History of Surfing. “The sport has been irrevocably, completely, fundamentally changed from what it was.”

The pool's location was undisclosed, but savvy Reddit users outed it within hours by cross- referencing freeze-frames with satellite images, Google Street View, and real estate records. The wave was not in the Australian outback or at the tip of Patagonia but in California’s San Joaquin Valley, between Fresno and a massive I-5 cattle yard that makes vegetarians out of passing drivers.

I arrive at the Surf Ranch on a typically chaotic day: Slater has two photo shoots followed by a meeting with Boyan Slat, the twenty-three-year-old Dutch founder of the Ocean Cleanup, which has raised more than $30 million to build a passive system that will leverage the ocean’s currents to break down the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Also visiting are a half dozen of Slater’s oldest friends. He homes in on me after lunch, his friends momentarily quiet as they contemplate humble-brag captions for their Instagram posts. (“Chance of a lifetime! Kelly, love you brother for this amazing experience.”) I’ve found it’s best to ignore Slater and let him come to you, like a house cat. Once you gain his attention, he makes almost uncomfortably intense eye contact.

When Slater asks for my take on his creation, I tell him the truth: His wave is surreal, addictive, sublime. But my reverence is laced with a nagging dread. He wants to know if I’ve read Ray Kurzweil’s prophecies of artificial intelligence outpacing humanity. “Just because you can build something doesn’t mean you should. Like the atom bomb,” he laughs, reading my expression. “Or like this pool.” It’s hard to tell if he’s joking.

Slater won his first world title in 1992, as a twenty-year-old rookie, which made him the youngest male surfing world champion ever. He won an unprecedented five titles in five years—and repeatedly dragged the sport into popular consciousness. He fought an octopus on Baywatch. Was named one of People magazine’s most beautiful people in 1991. Had an on-off romance with Pamela Anderson. Made a cameo in the animated penguin movie Surf’s Up. Modeled for Versace. Recorded an album produced by T Bone Burnett. Became known as “the Rebound Guy” on gossip blogs after being sighted with newly single celebs including Bar Refaeli, Cameron Diaz, and Gisele Bündchen. Designed a Pottery Barn line of furnishings for teens. Sang “I like beer” in Michelob’s recent Super Bowl ad. Bromanced Chris Hemsworth, Jimmy Buffett, Zac Efron, and Eddie Vedder. Played golf with Michael Phelps and Bill Murray.

By 1998, Slater seemed bored by winning, and he walked away from full-time competition on top, at twenty-six, aware that his victories weren’t making him any happier. He has since opened up about the childhood wounds that drove him: the time he slept in the driveway of his family’s Cocoa Beach, Florida, home to escape his parents’ screaming, before his dad left for good when Slater was eleven. How he and his older brother took turns in front of the small oil heater in their low-rent apartment. How his mom would say that she sometimes thought of getting in her car and driving away, leaving the boys behind forever. How for years after that, he’d cling to her leg if she tried to go grocery shopping alone.

When I ask about his family, Slater sighs. “I’m still learning,” he says. “It’s a never-ending process.” Slater began competing full-time again in 2002, but his comeback was thwarted by the death of his father from throat cancer. The following year, Slater lost the world title to twenty- five-year-old Andy Irons in the final heat. Yet as he forged on into his mid-thirties, Slater kept getting better. He beat Irons in 2005 and then won another three titles. After his tenth, a writer pleaded with him in The New York Times Magazine to retire in his prime and preserve his legacy. Friends considered holding an intervention. But Slater had already retired once. It didn’t suit him.

For one thing, competitions offer an opportunity to surf the world’s best waves with only one other surfer in the water. Most decent surf spots are crowded, and between events pros are forced to train amid packs of amateurs. Imagine if NBA stars could only practice by joining pickup games at the park. In search of solitude and quality surf, Slater obsessively studies global weather models, regularly chasing swells to remote Micronesia. When in California, he often paddles out after the sun goes down to avoid interacting with others.

In 2011, the world championship was decided in San Francisco, near my home. The day before his final heat, I invited Slater to surf a shark-infested secret spot down the coast, which requires a long hike to access. I told him the locals wouldn’t welcome an entourage. When he wavered, I left without telling him exactly where I was headed. Later, as the sun went down, I spotted a lone figure walking down the beach. It was Slater. He’d pieced together enough clues to figure out where I was. The next day, back in front of the cameras, he won his eleventh world title, becoming, at thirty- nine, the oldest champion of all time.

Since then, he has narrowly missed out on two additional titles. In July 2017, Slater broke his foot in South Africa, prematurely ending his season and prompting a new round of retirement rumors. As it turned out: Nope. “Surfing is what I’m best at,” Slater tells me at the ranch. “There’s a sense of identity to it.” In 2020, for the first time ever, the sport will be included in the Summer Olympics, in Tokyo. “I’ll be forty-eight,” Slater says. “I started competing at eight, so it’ll be four decades of contests. If I make the team, I’d be looking to officially retire after the Olympics.” An unremarkable Japanese beach break is the planned location, the equivalent of sending world-class skiers down a bunny slope. But Slater mentions that the venue could change—“if we get one of our waves built in time.”

Surfing has been clumsily packaged as a spring-break lark for a half century, from Gidget to the Beach Boys to Blue Crush. But the real money has been made in selling board shorts and T-shirts. The sport has been propped up by the marketing budgets of surf-clothing brands, and endorsements provide the bulk of a pro surfer’s income. Slater was sponsored by Quiksilver for twenty- four years, a period that saw the company surpass a billion dollars in revenue.

In 2015, a group of fans began prodding Slater on social media to investigate Quiksilver’s labor record and environmental impact. “I’d been getting paid for nearly thirty years by a company without really understanding how the clothing was made,” he says. And getting paid well: In 2010, as part of a five-year contract, Quiksilver reportedly gave Slater 3 percent of the company, a share then worth $22 million. But he passed on a lucrative contract renewal, and left with a question: What would it take to make surf clothing more responsibly? He partnered with John Moore, a lifelong surfer who’d developed Hollister for Abercrombie & Fitch, to start Outerknown in 2015. The brand rejects the prevailing logo-heavy aesthetic, instead drawing on postwar surfers’ understated cool.

Its clothing is fair labor certified, and some styles are made from recycled fishing nets, a values-driven decision that didn’t come cheap. Many surfers assumed Slater was cashing in on his name and that the eco-babble was just marketing. “When we launched Outerknown, we got ripped to shreds for our pricing,” Slater says. It didn’t help that the label was backed by the Kering group, owners of Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Puma. “Every stage of everything I’ve done, I’ve been called a sellout,” Slater says, adding that he “walked away from quite a lot of money to do this. I haven’t gotten rich off this thing.” Outerknown has since been able to reduce prices across the board. That same year, Slater also acquired the majority stake in Firewire Surfboards, another optimistic bet that surfers are willing to shell out more for sustainability.

“You would think that surf culture is open-minded, out of the box, individualistic,” he says, “but they’re the most conservative bunch in the world.” Firewire CEO Mark Price adds that “with Kelly’s investment, we were able to take margin hits. Most times when people take a majority share, they’re looking to flip the company. But Kelly’s setting up the next twenty- five years of his career.”

When I first interviewed Slater in 2008, he envisioned a future in which surfing might go mainstream. “Right now there’s something inherently missing,” he told me then. Slater wanted to expand the reach of the sport and connect with the sort of inlanders who already wore Quiksilver board shorts or Hollister hoodies. But his thirst for a wider audience wasn’t about money; it was about legitimacy. After Slater won his first world title, his manager at the time contacted Wheaties. He was told they only featured “genuine” athletes. “To them, I was just a beach bum,” according to Slater.

The Association of Surfing Professionals had in fact been cooked up by a few beach bums in the mid-seventies, in hopes of turning their passion into a livelihood. When Peter Townend became the first world-tour champion in 1976, he was presented with an impressive trophy in Honolulu. Photos were taken, and the trophy was promptly returned to its cabinet at the nearby Outrigger Canoe Club.

Slater spent his youth competing against these surfers, and they anointed him their baby-faced messiah. “This boy-man means a billion dollars to the industry,” Derek Hynd wrote in Surfer magazine in 1992. By the mid-aughts, Slater had become convinced that if surfing were to really grow, it would need to be completely retooled.

In 2012, the ASP was sold to an investment group fronted by his manager, Terry Hardy, and rebranded as the WSL. But the organization still wrestles with the same albatross: Good waves are hard to come by. They can’t be relied on to show up during a half-hour heat, even when all the weather variables align. Surf contests have two-week waiting periods, take three days to complete, and mostly involve athletes waiting around, staring dumbly at the sea. You certainly can’t plan on good waves appearing during East Coast prime-time viewing.

Slater decided that the sport needed a stadium and a more reliable playing field. He had dreamed about a competition-quality artificial wave since 1986, when he’d been paid to demonstrate surfing in a pool in Texas that produced waves that were “pitiful, even by Cocoa Beach standards.” Around 2005, he began seriously exploring concept designs. In 2008, he quietly hired USC professor and fluid dynamicist Adam Fincham. Fincham helped recruit a handful of engineers, and the group went to work creating surf from scratch in a Los Angeles warehouse. Slater and a partner funded the early research.

Fincham’s team spent years on whimsical renderings, complex computer models, and a small-scale prototype. But despite Slater’s involvement, investors weren’t willing to fund full-scale commercial development without seeing proof of concept. Rumors swirled that the project was a costly failure. Through mutual friends in Hawaii, Slater met Michael Schwab, the son of the mutual-fund billionaire Charles Schwab, who became smitten with the idea. By that point, surfing had been discovered and embraced by coastal elites searching for authenticity and a form of active meditation. Wealthy enthusiasts began sharing surf-vacation trophy shots on social media, and trips to exclusive surf resorts in Fiji and Sumba became popular with the Burning Man set.

Schwab had surfed in high school and started up again about ten years ago. “At first, my family didn’t really look at surfing as something that was okay,” the forty-two-year-old says. “It was for hippies, beatniks, people who weren’t doing anything with their life. But six years ago, my dad saw my interest and encouraged me to invest in what I was passionate about.” In 2014, with support from investors including Schwab, the newly incorporated Kelly Slater Wave Co. bought and drained an old water-ski lake in Lemoore, California, and began covertly building a working prototype to silence all doubters.

Previous wave pools used paddles or other brute-force means to push water forward and up into a breaking wave. Fincham’s team instead relied on a hydrofoil pulled through the water to create a soliton, a solitary wave approximating an ocean swell. Their approach wasn’t entirely novel—a Spanish company called Wavegarden also uses a hydrofoil—but Slater’s group had the know-how and the capital to build something bigger, more powerful, and more perfect than anything that had come before it. And they weren’t designing for an average customer. The wave was made for Slater.

When he visited the pool mid-construction in 2015, the immensity of the project terrified him. “I was in shock for half a day,” Slater says. “I almost couldn’t talk.” What had he gotten himself into? But once he tested the wave, it felt as if they had bottled lightning. Slater and his investors considered various business models. His technology generated fewer waves of higher quality than existing public pools, but the hydrofoil could also be dialed down to produce friendlier waves better suited for a wealthy beginner. Instead of charging by the hour, Kelly Slater Wave Co. began exploring a private-membership model similar to that of a luxury golf community in which an artificial wave serves as the centerpiece of a new development.

Michael Schwab isn’t the only deep-pocketed investor enamored with surfing. For the past few years, the WSL has poured unheard-of amounts into the sport. (The organization doesn’t release its finances and wouldn’t comment for this story, but some industry insiders estimate more than $40 million a year.) The WSL’s live webcasts now feature sophisticated camerawork and locations out of a James Bond film. The bulk of the funding has come from Dirk Ziff, a billionaire hedge-fund manager and heir to the Ziff Davis publishing fortune, who served as the WSL’s interim CEO last year. Some view Ziff’s involvement as a hostile takeover rather than an act of philanthropy. For most of its history, the world tour has been funded by major surf brands, but diminished profits have caused them to slash support. Without Ziff’s involvement, the tour might have crumbled. “There was a lot of fear when Dirk came in,” Slater says. “People don’t understand how much he loves surfing. He wants to keep the culture intact. But it’s a natural evolution to increase the visibility and reach of the sport.”

Seen through this lens, the WSL’s 2016 acquisition of a majority stake in Kelly Slater Wave Co. makes perfect sense. This month, the WSL will finally open the Surf Ranch’s gates for a public competition. Tickets start at ninety-nine dollars. The event will have a festival feel, with food and music. (Refreshments will presumably be provided by event sponsor Michelob.) Most surf competitions feature athletes vying against each other in one-on-one heats, as in tennis. This one will have five nation-based teams of two women and three men. For the first time, surfers will compete in identical conditions, waves arriving like clockwork.

A good ride in the ocean mixes the adrenaline spike of a hunter’s kill shot with a psilocybin- induced feeling of oneness with the universe. The rarity of these moments makes them that much sweeter. Such waves can be separated by years of patient waiting. In the interim, a surfer hones his or her skills and tracks meteorological conditions, often thinking about little else.

As it had for Slater, the water provided me with a sanctuary from a fractured family life. I often wonder about the things I might have accomplished if I’d been brave enough to walk away from surfing for a couple years, or months, or even one honest forty-hour workweek. I’ve spent my life chasing “perfect” waves, making shitty, selfish decisions in search of those transcendent windows when the elements come together. At fifteen, I rushed my family through my mother’s last birthday dinner so that I could get to the beach before dark. In the months before I became a parent, I worried incessantly that my daughter’s birth would coincide with an epic swell. I fake-smiled through her second birthday as I missed triple-overhead barrels.

Sometimes I marvel at how far I must have traveled across the faces of waves without ever getting anywhere. What has it all been for, now that once-in-a-lifetime surf is available on demand? Am I free, or stripped of my identity? “I’m in mourning,” Matt Warshaw tells me when I ask about the Surf Ranch. “I’ve come to believe Kelly’s wave is the end of days. We’ve traded magic for perfection, and it’s heartbreaking. Everything we are as surfers has to do with the scarcity and the struggle to find the perfect wave. I reject the idea that it doesn’t affect those who never get to surf the pool. It’s always there in the back of your mind. Any nobility to all the stupid stuff we’ve done for good surf is gone.”

Gerry Lopez, a Hawaiian master known for his ability to maintain perfect Zen while tube-riding dangerous surf, takes a more philosophical view. “You’re still trying to connect and be in harmony with this force of nature, even though it’s a man-made device,” he tells me. “There’s a spirituality about it, and I don’t think it has anything to do with what creates that energy.” Aaron James, author of Surfing with Sartre, says, “At best, it’s a supplement. The danger is trying to isolate only the peak moment of surfing.”

Even Slater felt conflicted when he brought his creation to life. “The first day we ran waves, I was of two mind-sets, if I’m being honest,” he says. “It was so amazing. But is it Pandora’s box? What does it mean for surfing? Almost in slow motion I was thinking, Can I wholeheartedly put my arms around this and love it?” He understands the worries. That by “counterfeiting nature,” he’s giving rise to a future of “class warfare” among surfers, the rich enjoying ideal conditions at the push of a button while the masses fight over limited resources at crowded, polluted beach breaks.

Slater wants to offer everyone a chance to surf his wave, but demand far outstrips supply. The day he revealed it to the world, his phone started pinging—three hundred texts, then four hundred, five hundred—and the begging hasn’t stopped since. “It’s like surf crack,” Slater laughs. Ex-pro Taylor Knox, who has known Slater since they were fourteen, says, “Once they get a taste, they’ll pay whatever. People are going to go bankrupt.” “It’s all been a selfish investment on my part to improve my own surfing,” says Schwab, who has already surfed the wave more than seventy-five times.

A second pool has been approved in Palm Beach, Florida, and more locations are in the works. There’s a three- to five-minute wait between waves, and visitors get a limited number of chances. Even for pros, the pressure can be intense, but most guests experience at least one mind-altering ride. “I cried after getting the longest tube of my career,” a retired pro surfer, who wishes to remain anonymous, tells me. “It was the best moment of my life. Better than the birth of my son.” The euphoria quickly turns to despair as they realize there’s no telling when they’ll get another wave like that again. “It’s hard to talk about tech being sacred,” Slater says. “But everyone who’s surfed the wave has had experiences that are sort of . . . sacred.”

It goes something like that for me. In the pool after lunch, a serendipitous mistake and quick recovery place me deep inside a tube. In a giddy flash, I realize that all I need to do is hold on. After five long, hallucinatory seconds, the wave ushers me to safety as Slater watches. I ride to the edge of the pool and step out. Slater tells me he was so sure I’d fallen that he started checking his phone. He only looked back up when he heard others hooting. “You’re done!” he says. “No, really. You’re not going to get a better one than that.” After a few minutes, Slater wanders off for another photo shoot and I sneak back into the pool, hoping someone else will fall and I’ll get one more perfect wave. But I never do.

In the first issue of Surfer magazine, published in 1960, founder John Severson wrote, “In this crowded world the surfer can still seek and find the perfect day, the perfect wave, and be alone with the surf and his thoughts.” Technology has been encroaching on this picture ever since. Decent waves and crowds are now a package deal, thanks to increasingly accurate forecasts and live-stream cameras. A swell’s arrival is anticipated and discussed just as snowstorms and hurricanes are on the Weather Channel.

Apple Watches have brought connectivity to the lineup, and in San Francisco it’s becoming more common to see work emails answered in the water. Many surfers spend more time checking the conditions online than actually surfing, and when they do surf, a GoPro or a drone buzzing overhead ensures that not a moment goes by unrecorded. Mixed into the concrete below the surface of Slater’s pool is a foundational assumption that nature can be replicated and even made better. Maybe that’s the truth, our shared inevitable future, and I’m just not ready for it. I want to go on believing, for at least a little while longer, that some things left over from our atavistic past don’t need to be optimized or augmented to continue being worth our time and attention.

The last wave of the day is created at 4:00 p.m. Then everyone moves to the hot tub, wetsuits still on, for margaritas. The only salt is on the glasses’ rims. Slater and his friends laugh and snap selfies as the staff starts a barbecue and a campfire. Before I leave, I invite him to rejoin me at the desolate beach we surfed together in 2011. Rare circumstances have converged, and tomorrow’s forecast promises good surf. Slater politely declines; he has another crew of friends visiting the Surf Ranch the next morning.

I drive north into the night, arrive home past midnight, sleep for a few hours. Back on the road again at 4:00 a.m., I reach the coast before dawn. As I hike down to the beach, my phone loses its signal. I can’t see the waves yet, but I can hear them. The rising sun dabs a bloody red on the surface of the water where I paddle out. An inquisitive seal bears witness. It’s the type of California day we used to call perfect. But after surfing Slater’s pool, I notice all the imperfections: misplaced wind chops, unpredictable warbles.

Back at the Surf Ranch, they’re summoning the first wave of the day. Slater’s probably riding it as his friends cheer from the sidelines, eager to take their turn.

I look to the horizon, waiting.